China is swiftly increasing its presence in the European electric vehicle market by capitalizing on a well-integrated value chain and substantial government backing. As Europe aims to achieve its 2035 goal of zero sales for Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles, can its automotive sector keep up, or will Chinese manufacturers take the forefront?

Europe’s 2035 obstacle: a race against the clock

In June 2022, the European Parliament voted to prohibit the sale of new Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles within the European Union (EU) by 2035. The goal is to reach carbon neutrality by 2050 by significantly cutting emissions across various sectors, notably transportation, which accounts for 60% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Europe. This timeline presents considerable risks to the automotive industry in Europe, especially for local car manufacturers.

Currently, the European automotive landscape is still largely dominated by Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles, which represent about half of sales in 2024. Additionally, hybrid (HEV) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEV), which have seen notable sales increases in Europe, make up 38% of sales in 2024. Starting in 2035, only battery electric vehicles (BEVs) will be allowed for sale, yet over 85% of car sales today do not meet this new regulation. Moreover, BEVs only accounted for 13.5% of total sales in the previous year, ranking third by powertrain. To meet the EU’s target of achieving 100% BEV sales, an annual growth rate of 14% for BEV sales is required starting this year—significantly higher than the -5% decline recorded in 2024 compared to the previous year.

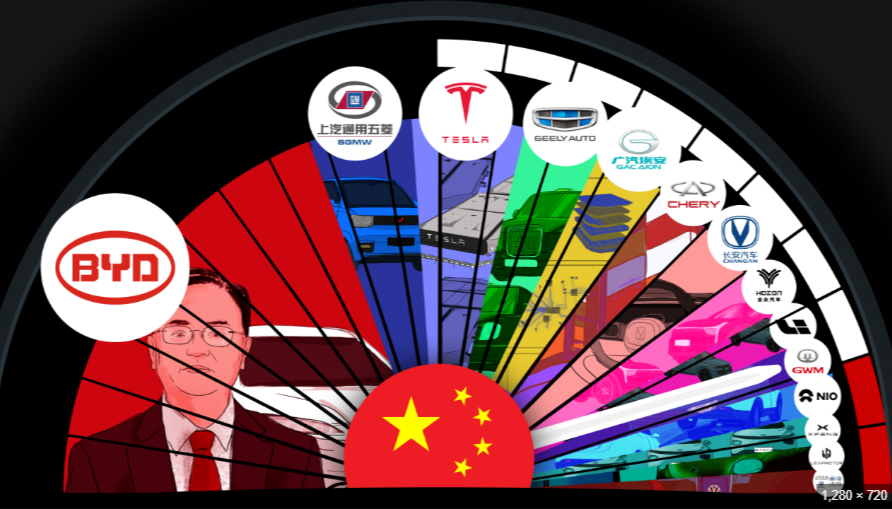

China’s Competitive Edge in the EV Industry

Conversely, many Chinese automotive firms—both manufacturers and suppliers—have gained significant expertise, especially in the electric vehicle (EV) sector. Bolstered by government support from Beijing, Chinese battery and electric vehicle manufacturers have forged a strong value chain since the early 2000s, covering everything from the mining industry (upstream) to the final assembly of EVs (downstream).

China plays a substantial role globally in the extraction and supply of critical raw materials, holding numerous mining assets internationally and producing around 60% of the world’s refined lithium supply, for instance.

The development of an extensive vertical value chain—encompassing extraction, refining, and manufacturing—coupled with financial support from the Chinese central government, has enabled the emergence of a leading Chinese electric vehicle industry. Chinese manufacturers have created a diverse array of products, enhanced production capacities, and invested heavily in research and development. Facing intense domestic competition and engaging in a price war, these manufacturers have progressively reduced their production costs and, as a result, their selling prices. Consequently, EVs in China tend to be two to three times less expensive than those sold in foreign markets.

Can Europe Imitate the US-Japan Model?

From a European standpoint, there is a clear danger that domestic manufacturers will be overtaken by their Chinese counterparts, who are better equipped to comply with the 2035 timeline. The European Commission is tackling this challenge by implementing tariff surcharges to lessen the price disparity.

To uphold a thriving automotive industry within Europe, it must cultivate sufficiently competitive electric vehicle manufacturing capabilities to compete with Chinese rivals. Nonetheless, the primary challenge lies in the considerable difference in production costs between Europe and China. The introduction of tariff surcharges seeks to diminish the gap between the EU and China. These newly imposed trade barriers may be reinforced over time and are seen as part of an industrial strategy of “reverse offshoring.” This strategy echoes that adopted by the United States during the 1980s in response to tough competition from Japanese firms. By combining import quotas with a monetary system adjustment favoring the U.S. dollar, Washington motivated Japanese manufacturers to set up production facilities on U.S. territory to gain access to the American market. As a result, ten years post the Plaza Accords signing, Japanese vehicle imports into the U.S. had dropped by 55%, supplanted by Japanese car manufacturing taking place within the U.S.

In theory, European policymakers might find this model appealing. However, European negotiating power appears to be quite limited at present. In the U.S.-Japan scenario, Washington held a position of strength over Tokyo since 1945. Additionally, in 1980, the American market constituted 45% of Japan’s overall auto exports. Moreover, the tariffs implemented by the EU do not entirely close the price gap between European and Chinese EVs. For instance, the Chinese company BYD shows a price difference of approximately 80% to 100% between its models sold in China and those marketed in Europe. To actually narrow the price disparity between the Chinese and European markets, surcharges in the range of 45% to 55% would be necessary.

What lies ahead for the EV market in Europe?

The European market will continue to be a major focus for Chinese automobile manufacturers in the medium term, as they look for alternatives due to the slowdown in their home market and are ramping up investments in various global regions. To avoid customs barriers, Chinese manufacturers might choose a hybrid approach, which entails assembling cars from kits made in China. This is exemplified by the collaboration between Stellantis and the Chinese firm Leapmotor, which will produce its T03 electric model in Poland.

The total number of vehicles in the UK has risen by 1.4% to 41,964,268, with the number of active cars increasing by 1.3% to 36,165,401.

During March 2024, the new car market grew by 12.4%, totaling 357,103 units.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) constituted 19.6% of this market.

Van usage also hit record highs, increasing by 1.8% to 5,102,180 units.

Since 2015, over one million vans have been added to the roads in the UK.

At the same time, the volumes of heavy goods vehicles remained steady, showing a slight decline of 0.1% to 625,509 units.

The number of buses and coaches also decreased by 0.1% to 71,718 units.

The vehicle parc in the UK, representing the total count of vehicles on the road at a particular time, is progressively decarbonising, with a 34.6% increase in plug-in vehicles (both BEV and plug-in hybrid), which now make up 5.1% or 2,157,360 vehicles.

BEVs recorded a 38.9% growth to 1,334,246 units, taking up 3.7% of active cars, a rise from the figures in 2023.

Petrol-powered vehicles continue to lead, increasing by 1% to 21 million, while diesel vehicle numbers fell by 4.4% to 11.6 million—marking the fifth year in a row of decline for diesel.

The transition towards lower and zero-emission technologies has resulted in a 1.6% decrease in average car CO₂ emissions, largely due to a 5.6% reduction in emissions from company cars, spurred by fiscal incentives and manufacturer commitments.

The average age of cars on UK roads has grown to 9.5 years, up from 9.3 years in 2023, with over 43.4% of the total parc exceeding a decade in age.

This trend predates the implementation of lower-emission Euro 6 technology, underscoring the necessity for consumer incentives to boost decarbonisation.

The commercial vehicle parc is also undergoing decarbonisation, with a remarkable 81.8% surge in zero-emission buses to 3,494 units, which now constitute 4.9% of buses in operation.

Battery electric van numbers increased by 31.6% to 80,476 units, representing 1.6% of the parc. Electric truck usage has also grown, although they make up less than 0.1% of the entire fleet.

SMMT chief executive Mike Hawes remarked: “Britain’s vehicle parc is expanding, providing vital mobility for the country while mitigating its environmental impact. Nevertheless, there is potential to accelerate environmental enhancements as drivers are keeping their vehicles for longer, averaging one and a half years longer than five years ago.

“Motorists require additional incentives and increased confidence in infrastructure investments if we are to substitute the high number of older, high-emission cars with zero-emission options. Achieving this will ensure the nation remains mobile while boosting economic growth for all businesses reliant on road transport.”